LIPPINCOTT’S: A CENTURY OF SERVICE TO MOUNT HOLLY

A FOUNDATIONAL BUSINESS THAT PROVIDED CRITICAL PRODUCTS TO GENERATIONS OF RESIDENTS

By Joseph Jones. Guest Writer For The Mount Holly Reporter

EDITOR’S SUMMARY: The only thing I have added to this story is 1915 Sanborn map which establishes that Lippincott Supply was in fact on the ground in Mount Holly in that year. Since Lippincott’s only sold its business to Athenia supply in the last couple years, the map demonstrates that Lippincott’s was here for over 100 years. I am happy to have known Joe Jones since shortly after my 1988 arrival in Mt. Holly. That’s when I got it in my head that I would renovate the house at 47 Garden Street and began visiting Lippincott Masonry Supply on the regular. By then, Joe ran the place and they really did have everything you needed to fix a 150 year old house. I quickly realized that all the people there were smart, fun, and best of all, they didn’t treat me like the lady at Madden’s. Joe wrote this story about the last fifty years of Lippincott’s business and it was the easiest edit job I ever did. Not a word has changed. Enjoy.

In the ‘60’s we referred to our family business as The Coalyard. Lippincott’s was a little store-front on Washington St. then, two parking-spaces wide out front, with driveways to the back almost hidden between neighboring houses and the Imperial Hotel. The most important early asset was the railroad siding that left the main track in the woods across the street, crossed the mill race, and ran along the building to the widening rear yard. Some of the old promotional materials – calendars, ink blotters – gave the address as “Washington St. & the Railroad Crossing, Mt. Holly.”

The railroad delivered coal. The siding was almost within arm’s reach of the window next to my grandfather’s desk, and I remember sitting on his lap and feeling the building shake and shift as a train trundled by, possibly exaggerated somewhat by a playful rocking in his knees. The yard sloped down from the street enough that the tracks ran out flat over concrete abutments, forming bins six or eight feet deep where coal cars dumped their loads. There were silos, too, made of curved concrete blocks, and loaded by augers with electric motors. There is an apocryphal story that someone would sometimes have to break a jam-up of frozen coal at the bottom of the silo by standing on it and chopping at it with a heavy, pointed “tank” bar until it released, and then would have to fold their arms and ride the load through the chute into the truck.

Back then Mt. Holly was full of bustling businesses. Near the crossroads of High and Mill Street were the W.T. Grant Store, Checker Athletic Store, two banks, two drugstores, and four clothing stores (two men’s, two women’s), the old Acme, two gas stations, and more. Closer to us, on either side of the Rancocas Creek, were Eagle Dye, Miller Ford, French Lumber Co. and Hollyford. The rail siding continued beyond our yard, crossed the meandering creek again, and dead-ended at Hollyford Coal & Ice, a competitor in the coal business and fellow-practitioner of the old model of combining products – ours were coal and masonry supplies – that kept us busy in every season. On the very day when it got too cold to mix mortar and concrete, people would call for coal and, after World War II, heating oil.

The last remnant of the coal era, besides the bins that now hold sand and gravel, is the scale next to the store, built for coal wagons early in the 20th century. Still there, still working, with a current State Weights & Measures inspection sticker on it, it is a simple, mechanical balance beam, not unlike a high-school chemistry-class scale, with a wooden deck outside. It once had a roof, and a platform on the far side with a few partially filled coal bags and a pile of empties; inside was a brass arm with hash marks and numbers and sliding counterweights. Coal was sold by the whole ton, and if the load in the truck was short, the men would empty bags into the truck until the weight was correct; if it was over, they would shovel some off into bags and leave them on the shelf. Mrs. Customer got what she ordered – no more, no less. Alma, in her hair net and sensible shoes, who answered the phone and typed, and called my grandfather “The Mister,” was intensely proud of being a Certified Weigh-Master.

In a prominent place just inside the front door was the office heater, showing off a Motor-Stoker, a small auger that fed a slow, steady supply of coal to the fire automatically. The men who stood near it, enjoying the warmth while they waited for the next load, had a reverse raccoon look from the coal dust on their faces. My mom talked about Grandad, who wore a white shirt and tie to work, coming home with a rim of black on his collar. He changed into a clean shirt and a different tie for dinner.

By the time I visited, the coal heater had been replaced by an oil boiler, thanks in no small part to Charlie, my grandfather’s “Associate”, who pushed for the “new, modern, clean oil heat”. The coal silos visible in many an old photo of our part of town came down, replaced by three rail-car tanks taken off their wheel-trucks and set on concrete feet. Later came a 200,000 gallon tank, thirty feet high, and painted blue, with “Lippincott’s Fuel” in yellow letters. The color scheme was adopted from our supplier, Sun Oil Co. – Sunoco – who paid to have their logo on the tank and on our trucks.

In the summer, we sold building products. Beginning with slate, terra cotta, quick-lime and other plaster products, and sand and gravel, the line was modernized along the way with wallboard (Sheetrock is a brand name), roof shingles, insulation, aluminum and then vinyl siding, along with gutter and downspout. I began working during college summers as a helper, hand-unloading loads of wallboard – 110 sheets, 4ft by 12ft, two at a time – often up a bouncing plank across an unfinished porch; or 648 cinder blocks, handed down from the flat-bed, carried down a dirt ramp, one in each hand, and re-stacked into cubes on the floor of a basement-in-progress. Later, some of those product lines were taken over by specialized outlets and then by the big box stores; meanwhile I had begun to move into an office role, tutored by Charlie, and we continued to look for the latest thing to stay diversified. We went through wood-stoves as they replaced fireplaces in popularity, and a couple of other false starts, until a salesman from one of our block suppliers came in to promote concrete pavers.

Pavers were something new that had blossomed in Europe, promising to replace brick and stone walkways and patios with more choices of color and style, and easier and more scientific installation. I had seen a massive paver project underway on the waterfront below our hotel window in Quebec City, on my honeymoon, and that helped convince me. People were interested, especially do-it-yourselfers, and they crowded our lot for how-to seminars on Saturdays. Soon there was a growing market among landscapers, who built up their grass-cutting and fertilizing businesses with custom installation of more and more elaborate outdoor designs.

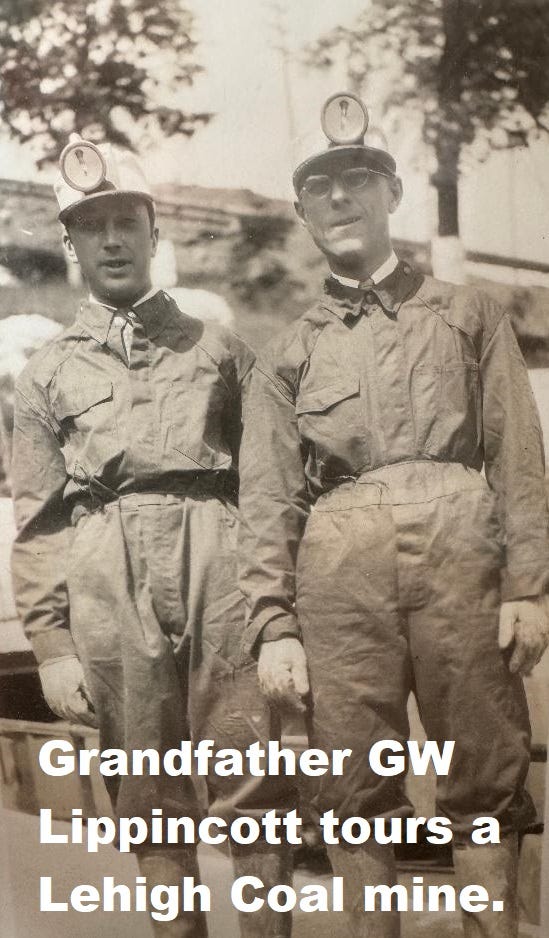

My grandfather, the eponymous George W. Lippincott, had taken over the business from his father, the founder, Stacy B. My mom worked in the office and my dad, a farmer, drove an oil truck in the busy winter season. When G.W. retired, my mom and dad, who had sold their farm, took over in turn. After graduation and some time trying other things, I was drawn back toward the next generational change. And, like my parents and Charlie, and my grandfather before them, I always had my eye on the next improvement.

Along with the product lines, we modernized our handling systems. The old warehouses had been built close to the rails so that materials could be walked from boxcars and flat cars right onto the raised warehouse floors. Sand and gravel came on flatcars with three-foot sides, and were unloaded by hand, with a big coal shovel, which was the size of a snow shovel, and scoop-shaped: full, it might weigh forty or fifty pounds. Charlie and my dad introduced the first fork-lift and the first front-loader tractor, and began replacing the warehouses with ground-level concrete floors and enough room to maneuver inside. The old flatbed truck that we had unloaded by hand was replaced with a boom truck.

We expanded our footprint when properties around us went up for sale. Along with a bigger store and double the warehouse space, we added the parking lot that, soon enough, wasn’t big enough for a busy Saturday, and changed the layout so that the tractor-trailers that had replaced the trains could wheel in and around our yard and out again. Eventually, the big oil tank was more than we needed and required upgrading to meet modern rules, so we took it down and remediated the problems left by the less careful habits of the old days.

For me, from my first visits as a school-boy, the best thing about Lippincott’s was always the people. Despite my cynical adage that young people who say they want to work with the public obviously haven’t tried it yet, I had found that the customers – and my co-workers – fascinated me. Snarling old contractors bit my head off the first time we met and thereafter called me “Joe-boy”; elderly ladies in cotton day dresses dropped off their monthly fuel payments and stayed to chat; people called in the middle of the night to say they had no heat.

The people at the coalyard greeted my sister and me with the gentle indulgence of the farmhands in “The Wizard of Oz”. My grandfather would jerk his ubiquitous fedora a little sideways, bend at the waist, and offer a handshake: “Here’s my five.” Alma always made a fuss over us, and sent us cakes for our birthdays. Art, who seemed like a giant, was almost a head taller than my dad, was known to carry two 94 lb. bags of cement at once, and retired early with a bad back; Bill, half Art’s size, taught me to deliver oil, to always stand within arm’s-length of the shut-off nozzle when pumping 60 gallons a minute into a house, and to always have dog biscuits in your pocket; Bundy, who never had a driver’s license and worked at the yard into his 80’s, would mumble, as we unloaded wallboard, “106 more to go… 104 more to go,” all the way to the last bundle, and say, every time, ”here’s the one we were lookin’ for!”. Charlie, a smiling, gentle-voiced man, who partnered with my parents when G.W. retired, taught me the ins and outs of the business – how to calculate and schedule automatic delivery of oil, how and when to order a load of block, and mostly how to talk to customers.

Over the years it seemed harder to find people who would stay long-term, or whom we would want to keep. But there were some, and they made Lippincott’s Lippincott’s: Sherri, who kept the books and kept the customers happy, and whose recommendation from a former boss included “don’t let the tattoos bother you”; Dave, who ran the yard from the seat of a forklift and kept better inventory in his head than I could in the computer; Pete, grumpy and scary-looking but dedicated to customers, especially the rank and file who came in to pick up supplies; Jim, who could fix trucks, repair the building, cut stone, and charm the customers designing their fireplace, usually all at the same time.

The latest generation of my family found themselves drawn to other pursuits. I’ve often wondered if, in spite of my good fortune, I grumbled too much at the dinner table. So, when I was ready to retire, I had to look for a buyer. I talked to a lot of potential candidates, but one way or another, the fit was not right. Finally, Lippincott’s Supply and Athenia Mason Supply from Clifton, NJ, found one another. Bringing along both the advantages of a bigger business and the attentions of a second-generation family of three siblings – and, I’m happy to say, retaining nearly all our crew – Athenia has begun the next era in the evolution of an old Mt. Holly institution.