Historic House a Focus in Preservation Debate

Local Developer Renovates Historic House Without Preservation Commission Oversight

By Rebecca Nieves, Special to The Reporter from The College of New Jersey

Nestled at the corner of Garden and Clover streets, an extraordinary home has quietly stood, enveloped in vines and surrounded by overgrown shrubbery. Built in 1854, the home with a distinctive Victorian design has survived despite the recent years when it wasn’t maintained, resulting in a leaking, rusted tin roof and peeling paint.

This quiet decline is familiar in older communities where middle-income residents struggle to maintain aging properties. It’s a pattern often referred to as “demolition by neglect”, where homes deteriorate to a point that preservation becomes impossible. For 427 Garden Street, this seemed inevitable.

But after a retired Mount Holly police officer, Frank Pallante, purchased the site in December of 2024, social media chatter about the building intensified. Predictions of a complete building teardown turned out to be unfounded, but how faithfully the historic features of this 171-year-old structure would be restored was a subject of concern amongst residents.

Mr. Pallante's arrival at the site coincided with a debate in Mount Holly about the town’s historic preservation rules and what it means to preserve a place with historical significance [see https://www.themounthollyreporter.org/p/editorial-going-going-gone] A debate in Town Council chambers is ongoing about how much of any historic home’s identity must be retained by law. This is a difficult balance to strike when owners are faced with limited budgets and years of decay.

Pictured: Damage to 427 Garden Street from leaking roof. Photo Credit: Ergo Real Estate Co.

A Historic Place that does not protect its historic places

Mount Holly welcomes travelers to town with a message about its historic identity. Yet the town dismissed all members of the Historic Preservation Commission (HPC), which still exists technically but no longer meets. Likewise, the “Certificate of Appropriateness” required by law still on the books is no longer issued for each project in the historic zone. This issue was addressed at a recent Town Council meeting when the Solicitor announced that the law will be modified to roll back what he and Town Manager Brown consider excessive. The rewrite has been talked about since mid-2024 and is still at least months away. In the meantime, renovations of historic properties, such as 427 Garden Street, proceed with no HPC oversight for preservation.

Historian Fills in the Blanks for The Children's Home

According to Eric Orange, a Burlington County historian, the home used to operate as a boarding school for kids during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was among several boarding schools in Mount Holly at that time.

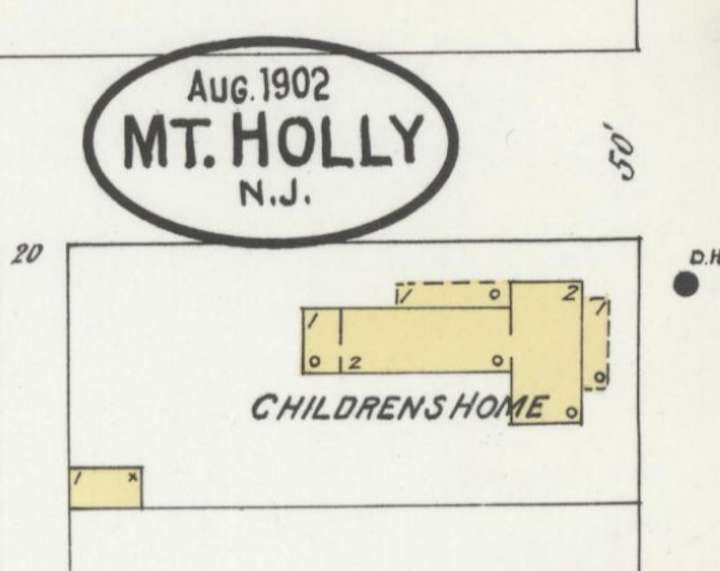

Pictured: A 1902 Sanborn Fire Insurance map labels this building as the “Children's Home”, indicating its operating on Garden Street during the early 20th century.

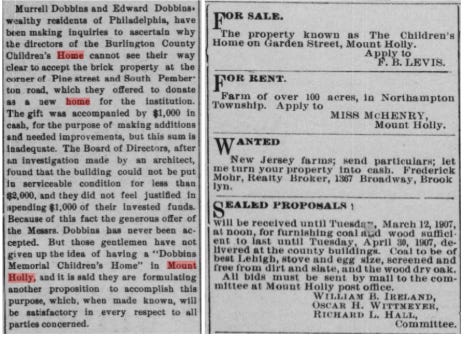

In 1905, Edward and Murrell “Mary” Dobbins, two prominent residents, began efforts to donate a property for the Burlington County Children’s Home. After Edward’s passing in 1906, his will ensured the donation was carried out. In 1907, the Mount Holly News reported the sale of the property on Garden Street. By 1908, Sanborn maps no longer labeled the Garden Street building as a children’s home, suggesting it either ceased operations or was relocated.

Historical records strongly suggest that the Burlington Children’s Home and the Children’s Home on Garden Street were the same institution. The Dobbins family arranged for the relocation of the Burlington Children’s home in 1906, and by 1908, Sanborn maps no longer list a children’s home on Garden Street. However, due to the lack of definitive property records, a clear connection between the two locations remains unverified.

On the left: A 1905 news excerpt from a former local newspaper, “The Mount Holly News”, describes the Dobbins family interest in the Children’s Home.

On the right: A 1908 news excerpt from the same newspaper advertising the Garden Street home for sale.

While its history remains elusive, the legacy of the building endures. The pale pink home at 427 Garden Street, with decorative corbels, red trimmed windows and delicate pink and red accents along the portico columns, continues to evoke admiration from local residents. Its rare blend of symmetry and detail speaks to the home’s historical charm.

Today, the property is being renovated by Frank Pallante, a retired local police officer who has recently completed work on a number of abandoned historic houses along Washington Street where the dilapidated structures received much needed attention.

“He’s trying to make the house livable so he can sell it to somebody, and ultimately, the people who live in it may not want radiators for heat and things like that. Everybody wants air conditioning and things of that nature,” said Orange. “The whole house is historic, and it’s going to look historic,” said Orange, who is among several residents praising Pallante’s current efforts. “But if it doesn’t… what was the other option?”

Pallante was contacted for this article and did not want to provide comment. But he shares construction updates on his ‘Frank’s Flips’ Instagram page that showcase the “before" and “after” of his projects. He completes full gut renovations, meaning the interior is rebuilt with modern utilities.

It's the exterior modifications that raise concern with some locals regarding preservation. In the past, when the HPC existed, Mr. Pallante would have needed to reach agreement on architectural details with the Commission before a construction permit was issued. But since that no longer occurs, government construction permits are issued based only on Uniform Construction Codes for safety.

Above: A Pallante Renovation on Washington Street. The Mansard roofline was maintained and the simulated “6 over 6” windows paid homage to the historical look.

House flipping is often focused on speedy, less expensive renovations for resale and profit that can erase some original historic features. And that outcome would be at odds with the HPC focus on preserving a property’s original historic character. There is a tension between typical flipping goals and the HPC “Certificate of Appropriateness” process which in general adds time and expense to projects. But preservationists say that the HPC process is a negotiation which seeks agreement with the redeveloper.

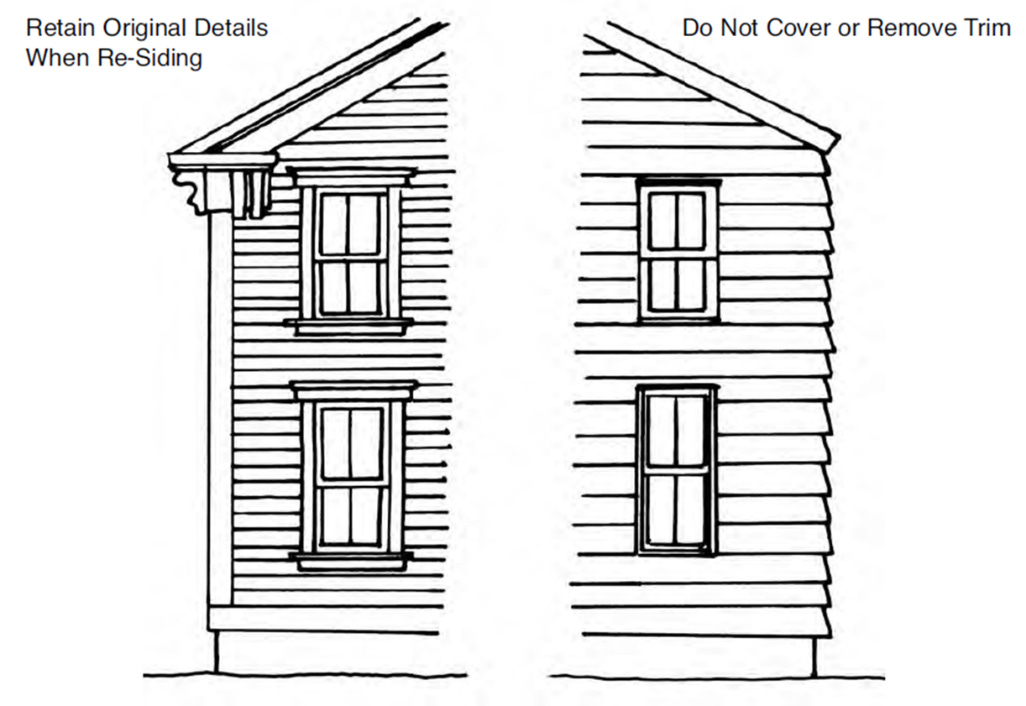

It's important because even small changes, like replacing original windows or removing and altering the decorative trim, can drastically affect a building’s character. These architectural features are often what give a structure its period appearance.

Photo Credit: Plainfield Design Guidelines

Former HPC Chair Discusses Former Preservation Program

Federal preservation guidelines, such as the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards, provide general recommendations but do not account for case-specific situations. This is where a historic preservation commission would come into play.

Many towns develop their own design guidelines that are specific to their localities, and when unusual circumstances arise, a HPC can review the case and provide guidance.

According to Amy Eversmeyer, a former Chair of Mount Holly’s HPC, the Commission would often review projects and provide detailed recommendations to owners looking to make changes to anything that was on the exterior of the home, such as windows, fences, siding, doors, or paint colors.

While there are still numerous historic homes in Mount Holly, without an HPC, property owners who might want to preserve features have only the federal guidelines to help them. And with no local body to advocate for historical sites, any redevelopment of the business district will likely cede preservation of the town’s historical identity to the notions of a developer.

In the case of Pallante, Eversmeyer said, “He is saving the house. I’m happy to see something is being done. But if there was a commission to work with him, we could ensure that it’s done the right way. There’s a lot of materials that are more available and more affordable today that will replicate what was there at no significant cost. Everything’s doable, and a commission is there to help you with that.”

Eversmeyer said that she hopes Pallante will preserve the woodwork of the home, and that he will pay special attention to replicating the windows.

The HPC also categorized historic buildings in the district as key, contributing, or non-contributing, determining which structures required protection and to what extent. Eversmeyer stated that “The Children’s Home” would be classified as contributing or key. The home is also within Mount Holly’s historic district, according to the Department of Environmental Protection.

Pictured: A map that shows where the historical district is in Mount Holly. The building in red with the blue box is the “Children’s Home” on Garden St. (LUCY - Department of Environmental Protection).

Cost Considerations and Funding

While true historical restoration can be costly, if Pallante rehabilitated the property for rental use and the home is part of a historic district, he would likely qualify for federal programs that aid in historic preservation efforts if he submitted an application to determine eligibility.

One of these programs is the Federal Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit program, introduced in 1976. It offers property owners a 20% income tax credit for rehabilitation costs, provided the work aligns with federal preservation standards and is aimed at income-producing purposes.

A resident of Mount Holly who wished to remain anonymous navigated the challenges of historic preservation said institutional support was crucial in helping her preserve the key features of her home.

She said that her and her husband were in their thirties in 2003 when we moved to Mount Holly. The historic housing here were frequently in a run-down state, but that meant it was affordable. And they were prepared to use ‘sweat equity’ to turn one of those houses into our charming home. Still, the prospect of replacing an ancient heating system and sunken foundation was financially daunting. But when thier realtor mentioned the 'loan to grant' program offered by Mount Holly, it not only gave them financing to get major things done right away, it also turned into a grant if they stayed in the home. They were eventually approved for 12K in foundation repairs and window improvement costs. And they still live in that home.

While Mount Holly is still a designated historic district, it is not a Certified Local Government (CLG), meaning it lacks access to additional resources, grant funding, and oversight tools that could help protect its historic properties. Without these safeguards, removing a certain percentage of these historic homes could result in the area losing its historic district designation, making preservation exponentially more challenging.

The lack of an active preservation commission means that “flippers” are not required to submit their renovation plans for review. If such a board were in place, it could ensure that renovation plans adhere to historical standards, potentially pressuring developers to preserve, or even replicate, the home’s original character.

True historical restoration is both costly and complex, often requiring specialized materials and craftsmanship that don’t always align with the financial constraints of house flipping. At the very least, flipping ensures that historic buildings aren’t entirely lost to time, offering a chance for preservation, even if it’s not always perfect.

Mount Holly is considering what balance to strike, and as is often the case, taking a very long time to make decisions.

For now, it seems that Mr. Pallante’s work will help contribute to maintaining the historic character that defines Mount Holly. But without a HPC, that outcome is left to chance.